People Matter: Encouraging Social Sustainability in the Wine Business

You know what “sustainable” means. Or do you?

When you see the word emblazoned on the label of a favorite wine, it conjures all things green: low-carbon footprints, renewable energy, and sleekly-designed planet Earth logos. “Sustainable” is just another way of saying “environmentally friendly.” Right?

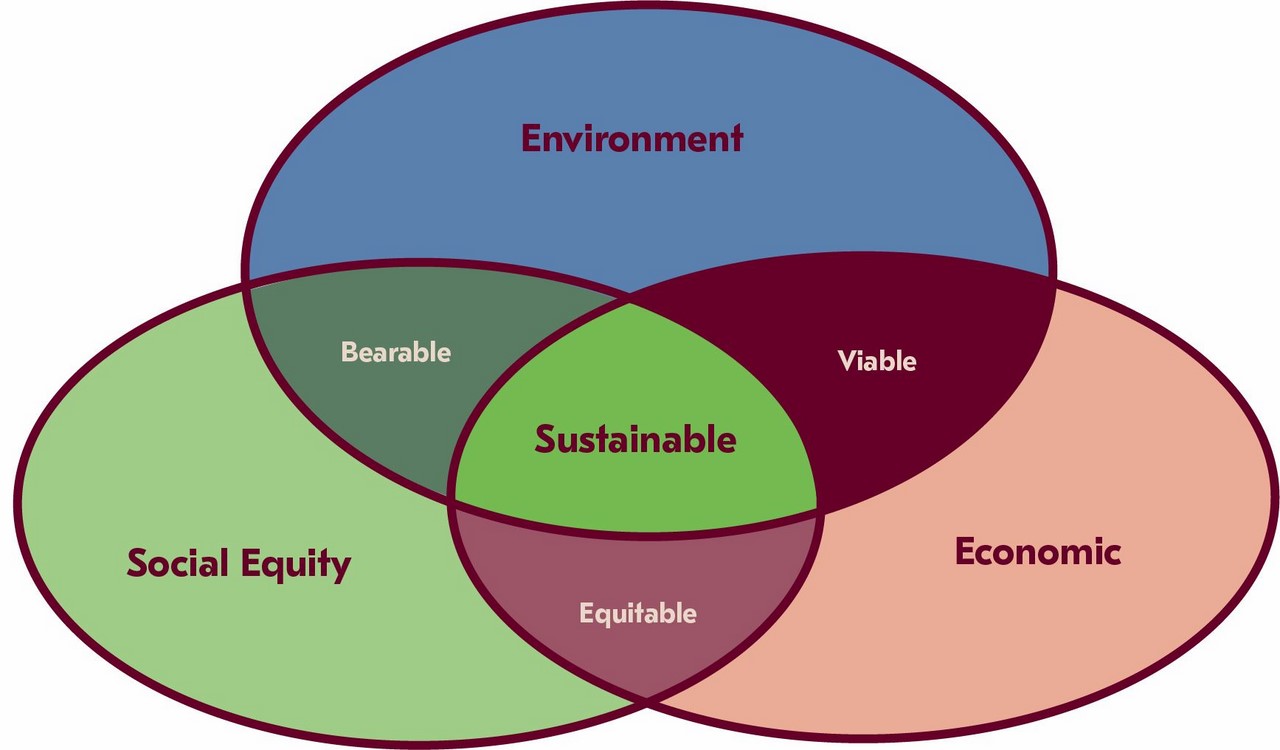

Well, that’s one piece of the puzzle. According to standards developed by the United Nations, sustainability is built on three pillars. One is indeed environmental. The second is economic. Most businesspeople prioritize the bottom line, so economic sustainability is usually integrated into winery business plans. Alas, fewer executives pause to consider the social aspect of sustainability.

We are talking, of course, about people.

WHAT IS SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY?

Social sustainability considers the practices and policies that are best for all people connected with the company—from workers to suppliers to community members. A socially sustainable company aims to cultivate diversity, quality of life, equity, and leadership. Examples of social sustainability might include: a company-sponsored education fund, daycare program, team-building retreat, or healthcare initiative.

The global sustainability standards are based on a 1987 United Nations document entitled Our Common Ground (a.k.a. The Brundtland Report). Prior, sustainability had been documented for at least four centuries. Despite its “buzzword” status, the concept is nothing new. Still, efforts to bring environmental awareness into the wine industry have intensified in the past decade. The result is an overwhelming array of sustainability certification programs—all heavily based on environmental standards. [Chart] Social standards often remain overlooked.

How might wineries and vineyards pay greater attention to the social part of sustainability? Which organizations are already making an effort? Could companies be held more accountable for how they manage and relate to people? In some corners of the industry, we find beacons that might just guide the way.

LISTEN WELL & BE PATIENT: SONOMA COUNTY WINEGROWERS

Sonoma County Winegrowers (SCW) has won considerable acclaim for their leadership in sustainable winegrowing. SCW has made trailblazing efforts to designate Sonoma County as the nation’s first sustainable winegrowing region by 2019. Executive Director Karissa Kruse has led the charge, very pointedly making social sustainability an integral part of the program planning.

“We made his big commitment to sustainability and were gaining a lot of traction and getting a lot of recognition for it,” says Kruse. “And we stepped back and realized that, with that recognition, came accountability: Are we pushing the envelope and really being leaders in sustainability?”

Kruse realized that most agricultural workers connected with SCW live in Sonoma County and were a permanent part of the local community. With this epiphany, her sense of responsibility grew, and along with her list of questions: “Are folks safe? Are they getting appropriate training for their job? Do they understand their rights? Are we really taking care of our employees and their families?”

The only surefire way to get answers was to take the questions directly to the community—and listen. Over eight months, SCW set up three different feedback sessions to find out what the community concerns were. Sessions were held in Spanish and in English. Vineyard managers, family farmers, grape growers, and wineries were all involved. Participants were paid for their time.

Based on the results, SCW decided to focus social sustainability efforts on two main areas: affordable housing and workforce development. “We wanted to pick one or two things that we thought would provide the most impact and that we could do well,” says Kruse. “If you try to do everything, nothing delivers.”

That was in 2016. Now, SCW is well on its way to enacting a social sustainability plan. In collaboration with local engineers and vineyard owners, they have drawn up blueprints and models for six different housing plans. By spring 2018, SCW expects to add 200 beds to the vineyards of Sonoma County. And a plan for SCW workplace development, including a partnership with the local community college and mentorships with wine professionals, will launch in January 2018.

Patience is key. “We can’t do it all overnight,” Kruse acknowledges, but her resolve is apparent. “I want it to be, like: If you want to work in agriculture, come to Sonoma County! We care about you. We want to take care of you.”

BUILDING COMMUNITY: NAVARRO VINEYARDS

Up north from Sonoma in Mendocino County, Navarro Vineyards has been implementing social sustainability practices for four decades. In the 1960s, Deborah Cahn came to Anderson Valley with her husband Ted Bennett to farmstead. “It was sort of part of the back-to-the-land movement,” says Cahn. “And it was filled with a lot of the idealism of the seventies: I can’t change the whole world but I can change my own little corner of it.”

Now, Cahn maintains a staff of 75 employees, all of whom (including harvest, bottling line, and administrative workers) are full-time and benefited. In an industry that relies largely on seasonal help, the Navarro employment model is an anomaly. “We’ve worked hard to diversify the jobs so that we can use full-time permanent staff,” says Deborah. “The guys who work in the vineyard also work partly doing bottling and sometimes in the shipping department, so that we can keep people hired full time rather than part time.”

This only happens with some skilled choreography. “It requires quite a bit of planning on the part of the supervisors to move people from department.”

The staff enjoys the job security and benefits of this model, says Cahn, but it helps the company, too. The fact that she is not continually replacing and rehiring employees saves money. Furthermore, she says, “I am sure that we have customers who buy wine because they like how we treat our workers. It reflects on how we treat our grapevines and how we treat our wine.”

The lesson? Social sustainability can be good for the bottom line.

Much of Navarro’s business philosophy is influenced by the founding couple’s time in Japan. Prior to launching Navarro with Deborah, Ted Bennett did a great deal of business in Japan and developed a keen admiration for the way his colleagues involved all levels of management in the decision-making. Thus was born an egalitarian spirit that still rules the winery.

“When we blend the wine,” says Deborah, “it’s not just the owners and the winemaker, but the people in the tasting room and cellar who are involved in the blending decisions. It’s not just a winemaker’s wine. There is a democratization of decision-making. A lot of those ideas came from observing Japanese management style in the 70s.”

An active member of the nonprofit Anderson Valley Housing Association, Cahn (like Kruse) is deeply concerned about housing for her employees. “Not a lot of people in the area have their homes where they work,” she laments.

“When you’re living in a small community, your kids are going to the same school as the kids whose parents work on the ranch. These are your neighbors. You want them to have good health care and enough money to send their kids to college and a decent place to live.”

Header photo by Maja Petric on Unsplash.